Beacons of Badassery is an interview series shining light on strong women.

After spending most of my life trying to prove that I’m strong enough to be one of the guys, I’ve realized that instead of trying so hard to fit a certain expectation, we should be redefining what it actually means to be strong.

These women are doing just that.

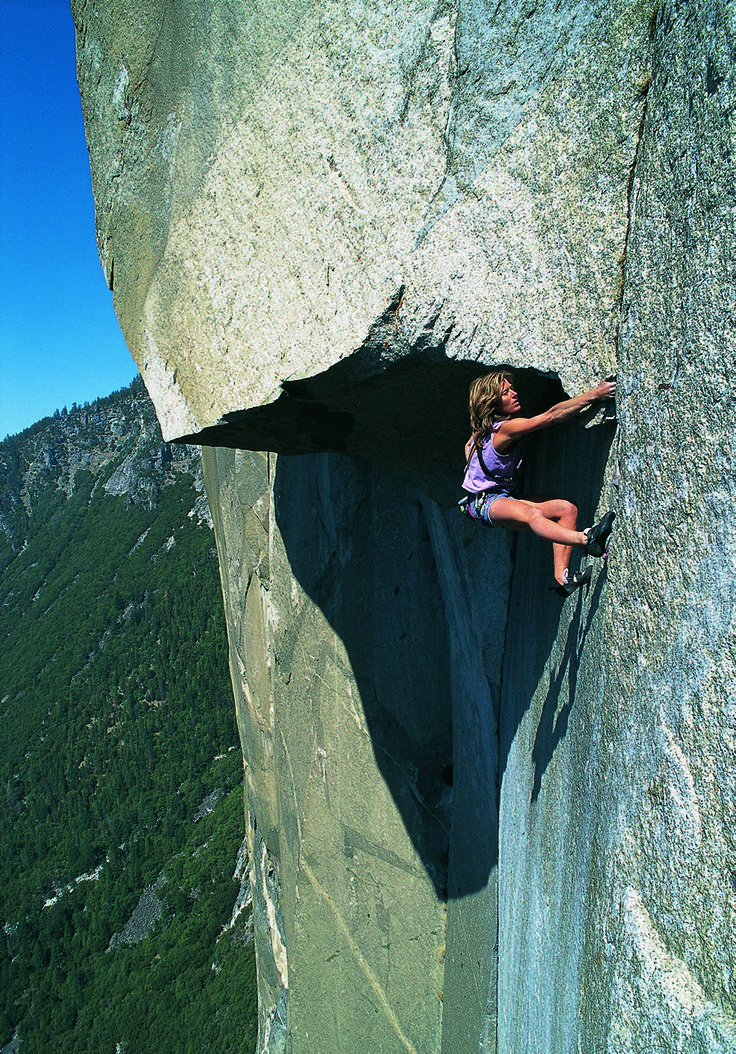

Beacon of Badassery: Lynn Hill

Just in case you don’t know, Lynn Hill is the first person to ever free climb The Nose. And she’s been an inspiration to climbers ever since.

One day, I randomly happened to be at the same crag in Clear Creek as Lynn, and I awkwardly went over to tell her that she’s awesome. After our chance meeting, she graciously agreed to an interview, so we chatted while hiking with her dog in Boulder. This was our conversation, edited and condensed for clarity.

Did you always feel it would be possible for you to free climb The Nose?

The idea of trying to free climb The Nose was a suggestion by a friend, John Long. I was just retiring from competition, and I had the fitness, I had the time, I didn’t have a job yet – I was going to make a decision about which way to go. I had a degree in biology, and I was going to go into physical therapy, maybe exercise physiology, so I could have at that point gone toward more of an academic career, but I instead decided, well, I’ll use this opportunity to do something great. Something that stands for my values, and that would be natural rock, my trad climbing roots, with my sport climbing fitness. And that was what The Nose required.

There were very few people at the time who had all of those experiences. There were people in Europe that had the sport climbing, but they didn’t have the trad climbing. The trad climbers in the US were too busy complaining about sport climbing to realize how much fun it is, and they missed the boat, and then I came along and did it. Because I had the vision, and I didn’t know that I was going to do it, but I had confidence that I could, and I certainly had a lot of motivation to do it.

There’s only a few sections that are extremely difficult, and 99% of it goes free for a large number of people. But the Great Roof, the Changing Corners pitch, and there are a few other technical sections – nothing that would be stopper, but those sections are very difficult in a way that’s much different than a sport climb that requires fitness and memorizing the sequence. This is memorizing the sequence on a very fine-tune level, because it’s very friction dependent and body position – you’re off by a millimeter – and therefore, it’s the most heady. It’s insecure, you feel like you could slip at any moment, but you just have to keep pushing and keep believing in yourself and focus on the next hold. And that’s what I did.

And I knew that it would be powerful, if I could do it all. So, you know, I think there’s a little bit of magic almost. When you want something for the right reasons, it’s much more powerful than if you just want the attention.

So you did The Nose to help prove to women that they could do this and believe that they could do it?

That’s why The Nose was important to me, because I knew it wasn’t just about my own empowerment. I had that, I’d learned that, that was part of my personal journey. And I learned that I could do things, and when people said that I couldn’t, that actually motivated me even more to prove them wrong. Because I don’t like that kind of attitude towards anyone.

If you’ve been suppressed throughout history, you know, my whole lifetime and before – it was better for me than it was for my mother, and it’s better now for the women of today, who think that they’ve achieved equality, but they’re SO wrong!

And they’re like, yeah, sure, I can climb cause Lynn Hill did The Nose, we can climb hard. But that’s different. That’s one element. That’s self-empowerment, which is great, that’s the first step towards empowering beyond just the individual.

Not having role models that have proven that & demonstrated that in their actions, it’s not nearly as powerful as somebody who says, okay, I think I can do this, and works on it, and does it, then you know it’s possible because it’s been done.

“It goes, boys!” Was that planned or did that just come out?

It came out in a conversation with John Bachar. We were going up there to take pictures, because he was a part owner of Boreal shoes, and I was sponsored by Boreal.

So we’re taking pictures and he was just joking around saying, “Yeah, gee, some day some guy’s gonna climb that route.” And I don’t know if he said it, or I said it – I think he might’ve said, “It goes, boys!”

And then he heard the conversation, like, objectively, and said that would be a good ad. So that’s where it came from.

You know, if you’d say that to a non-climber, they don’t know what you means. It goes? Where?

It means, it’s possible, essentially. It’s possible, boys.

You know why people like it, I think, is that for all these years that women were told they can’t do it, because they’re too weak, or they’re too delicate – people treated women like china dolls at a certain time.

And for a woman to be saying that to the boys – it’s possible, guys! It kind of flips it around. But with three words.

You’ve said you thought that after you did The Nose free then men were kind of less interested in it because a woman had done it so they were afraid to fail on something that a woman did.

I would say that men were intimidated to try and fail, but there weren’t that many men – or women – that were in a position to try something like that.

Jon Glassberg did this film (Climbing The Nose) with Jorg Verhoeven, who, they capture his ascent, and he starts out by saying, basically, “What is the mystery behind this route? Why has it only been done by a few people in twenty years?”

And the answer is, because it’s hard, in a way that you can’t just go up there with strong fingers and expect to just, you know, work out the sequence in a few days. Although, I must say, that’s what I did. I was much more fit back then, and, of course, motivated, but I only spent three days working on the crux, I mean, when I worked on the crux. And then I went down and sent it, in four days.

But, really, the ascent that, to me, was much more difficult, was doing it all free in a day, because you don’t have room for error. So I had to really follow my instincts and flow, not second guess myself, just keep the movement, keep as relaxed as possible, where appropriate of course, and tight in the abs. A lot of that delicate stuff is really just keeping up high in your abs tight.

Fear, you obviously have a functioning amygdala (unlike Alex Honnold, who we were discussing earlier)…

I do, and I respect that amygdala.

How do you handle that?

Well, first of all, I’ve been climbing for 43 years. If I take myself back to that 14-year-old girl, I was definitely scared that first day. But I had a right to be because I was leading my first climb. And it was a slab! So no concrete holds, just little edges and depressions, kind of low angle.

When I am in a situation that’s truly dangerous, which I try to avoid, I’m not a thrill seeker – yes, you get more adrenaline, it is exciting to be on something that’s slightly, well, let’s say, requires calculated risk-taking. But to be in a situation of true danger, I really don’t want to be. I don’t want to gamble with my life, to leave my son without a mother, especially now.

Did motherhood change you? In that way?

Of course it did! It changes you in that way, you definitely are less willing to take risks – I am anyway – because it’s not just my life.

But if I am in a situation like that, I’m very careful about waiting until the right moment to take an action, because you have a decision to make. You find yourself in that red flag, woo-ooo, we’re in a danger situation, and then you say, do I climb up, go to the next hold? Do I switch my body position because I’m not feeling it right now, so change your orientation to the rock, switch your feet, change your hands, maybe look wider? Because sometimes when you’re scared, you have tunnel vision, you don’t see the options. So you have to regroup at that point, usually that involves a nice big breath, breathing, and then opening your vision to what the solutions could be.

I’ve always been able to pretty much figure out the next move and go, and I haven’t taken a fall that’s been very dangerous.

Do you think that’s because you started climbing with trad, where the motto was “don’t fall?”

The first rule was “don’t fall.” And probably because we didn’t know if our gear was gonna hold. I mean, it’s usually pretty good if you get a stopper in a nice slot, but what if you’re on a crack that doesn’t really offer that?

In the beginning, we didn’t have cams, so you couldn’t just plug something in. Now you have either option – if it’s parallel-sided you have a cam, and it’s better like that if it’s parallel-sided. Whereas in the beginning, we were looking only for constrictions. We had hexentrics that worked more in a parallel crack, that did have a slight taper, but you still need some kind of taper for those to work. And they’re really not easy to place, so if you’re tired, and you can’t stop and hang onto a certain jam, and you decide to go further to get to a better jam where you can place protection more easily, but you fail before you can do it, then you’re taking even a bigger fall. So you learn to make these calculated judgements.

And we didn’t jump into 5.12. I didn’t even know 5.12 existed until many years after I’d been climbing. Because it didn’t really exist.

It might have existed in some corner of the world, like some part of France like in the ‘80s, but when I started it was 1975. Back then 5.10 was still the definition of human limits – like really? That was so shortsighted, I can’t believe that people thought that way. But if you think about history and all of the different social changes that we’ve seen, environmental changes, changes in science, everything, it’s always because people are opening up their minds and looking for solutions beyond the limitations that they’ve been told exist. But, you know, you realize that’s all just our own story. It’s what we tell ourselves that becomes the truth.

Do you think men and women climb differently a lot of the time?

Generally, yeah, we’re built differently. We have a lower center of gravity, so technically, we should be better on slabs, because the lower your center of gravity, the more stable you’re going to be. Whereas on an overhanging face, where it requires a lot of upper body strength, men’s upper body has more mass, and it’s better to have your mass up higher than down low, because your legs and your hips are going to be swinging out, and you’re using oppositional forces with your feet on these overhangs just to make sure that you’re feet don’t cut off.

So I would say in general, that would be true, but it doesn’t really matter, because I think no matter what your body size, build, sex, gender, whatever, you just want to adapt to the rock. Everybody has their unique artistry.

What would be your definition of strength, as a woman, not just physical strength?

Strength has to do with self-confidence and determination, because you might have a goal that is beyond where you are at now and that would require more fitness, more stretching maybe, more work on your mental game. That’s the kind of strength we’re talking about – when you’re in that moment of difficulty, are you telling yourself this is too hard for me, I’m not strong enough, I’m confused, whatever your self talk is that’s preventing you from doing it?

You can recognize that, and do what I call a mental shift where you recognize that you are either scared or don’t know what to do or pumped – pumped is a legitimate reason to fall because obviously, your strength is going to run out at a certain point at a certain level of difficulty, so that is something you can manage to a degree but not a hundred percent.

Anyway, you work on that part of your mental game, and pay attention, be conscious of what thoughts were happening in your mind, and why did you fall off? Was it because you actually let go because you thought you were too tired? But really, even when you’re tired, you can hang on for longer than you think. So you can make one more move.

But that to me is the strength of anyone, man, woman, it’s just about gauging things to the best of your ability and making the best decisions and not giving in to negative self-talk.

It should be objective. Relaxed face, not a grimace, because the grimace will make you tight. Just like when you put a smile on your face, that brings more joy, brings more happiness. So you try to not be judgmental against your self or anything else, you’re just there as a witness, almost like you’re watching a movie and you’re the player in this movie. Because then there’s no ego attachment, it’s more just observation, and I think that kind of mindset helps keep that judgment away. And judgement is connected to the self talk.

The idea is that people get so attached to they have to make it, and that pressure right there is going to keep them from doing it. Because it’s so important for them to tick it off, get to the top, that they’re not engaged in the actual process. They’re thinking about getting to the top. They’re thinking about maybe if I don’t get to the top I’m going to be mad, or I better do it this time, and that kind of pressure doesn’t really help your performance at all.

When you were going after The Nose, you didn’t put pressure on yourself that way?

The way that I looked at it was, since it hadn’t been done, I’m going to give it a valiant effort, and as long as I give my best effort, I’ll be happy. It might be that there’s one move I can’t do, or can’t do yet, or don’t see a way to do.

Because there are times when I look at a move, and I just walk away and say, I’m not going to do that move. I don’t have what it takes to do that move. And that’s just based on my experiences, and, you know, I don’t have to do every move, I don’t have to do every climb. Who does?

You have to put things in perspective and say I’m climbing because I enjoy climbing. There’s no reason to do something that’s going to be frustrating because you don’t have whatever skills, strength – it’s probably not skills, it’s probably more like not being able to reach something, you can’t jump to it, it’s not likely to happen.

When you’re all about tick-offs and your list of accomplishments and wanting to do certain named climbs because they’re famous, that’s a different mindset. You’re doing it for different reasons.

And I’ve come full circle. I have been a professional, I’ve been a competitor, and all that, and that was about getting to the top of the wall. And of course I played that game, and tried to win, but, at this point, it’s just like when I first started climbing, in the sense that I climb for the same reasons, of being outside in beautiful places, being with people I enjoy, laughing, heckling each other – it’s gotta be fun, right? And I like the puzzle. It’s like playing a game of chess, only your body is the tool.

Climbing is so great in so many ways, physically, mentally, if you will, spiritually. It’s the best thing I’ve got going in my life.

Huge thanks to Lynn for sharing her hard-earned wisdom – and for changing the definition of what is possible.

Find out more about Lynn on her site and follow her on Instagram @_linacolina_.

Also, be on the lookout for a series of videos she is creating on climbing technique. I got a sneak preview, and they really go in-depth to explain the physics of movement in a way that is easy to understand. And, seriously, who better to learn how to climb from than Lynn Hill?